Everett E Henderson Jr

University of Florida School of Architecture

Nexus: Handmade to High Tech Southeastern College of Art Conference

Sarasota, Florida/ Ringling College of Art and Design

October 9, 2014

My direction in the presentation of this paper is threefold. These three foci can be studied independently, but I have chosen to weave them together to gain a new perspective. The three perspectives are: The machine and the craftsman is where the artist is able to make a contribution. The hope for technology is the desire to make life easier and more pleasurable with new tools, machines, and technology. Prefabricated American architecture has the ability to be comprised of thoughtful, meaningful, and significant design. These three topics are woven together in order to gain a new insight. Currently, modern prefabricated architecture is re-presented as a new idea as it is being marketed as green technology, efficient use of space, high style, and flexible design. The truth is, is that prefabricated housing is not a new idea. It has been contemplated by many highly-publicized architects and designers such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Charles and Ray Eames, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and Buckminster Fuller for over a century. Prefabricated homes, for example, have been marketed and sold by Sears and Roebuck starting in 1908. The prefabricated homes sold by Sears were not designed by Sears, but the company did streamline the production and delivery of the precut pieces. The construction of the home was similar to a barn raising. While it may at first appear in today’s era of specialization that constructing a home by the average consumer seems daunting, yet to maintain a rural farm in the early 20th century carpentry and blacksmithing were necessities. The American public did not have the mindset that they could not erect their own shelter yet. The physical appearance and design of the Sears homes is nearly indistinguishable from the conventionally stick-built homes of the period. Prefabrication in the last ten years has been taking on a new life and is being marketed as: Smarter, Faster, Cheaper, Good Design, High Style and Flexible Design. It has been represented as a green way to create new home. The efficient use of space and therefore materials is one of the greenest aspects of prefabricated housing.

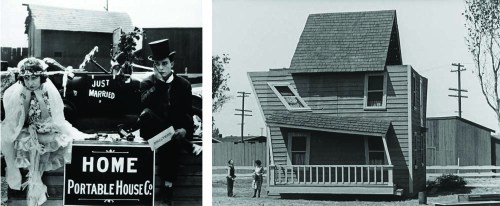

My direction in the presentation of this paper is threefold. These three foci can be studied independently, but I have chosen to weave them together to gain a new perspective. The three perspectives are: The machine and the craftsman is where the artist is able to make a contribution. The hope for technology is the desire to make life easier and more pleasurable with new tools, machines, and technology. Prefabricated American architecture has the ability to be comprised of thoughtful, meaningful, and significant design. These three topics are woven together in order to gain a new insight. Currently, modern prefabricated architecture is re-presented as a new idea as it is being marketed as green technology, efficient use of space, high style, and flexible design. The truth is, is that prefabricated housing is not a new idea. It has been contemplated by many highly-publicized architects and designers such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Charles and Ray Eames, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and Buckminster Fuller for over a century. Prefabricated homes, for example, have been marketed and sold by Sears and Roebuck starting in 1908. The prefabricated homes sold by Sears were not designed by Sears, but the company did streamline the production and delivery of the precut pieces. The construction of the home was similar to a barn raising. While it may at first appear in today’s era of specialization that constructing a home by the average consumer seems daunting, yet to maintain a rural farm in the early 20th century carpentry and blacksmithing were necessities. The American public did not have the mindset that they could not erect their own shelter yet. The physical appearance and design of the Sears homes is nearly indistinguishable from the conventionally stick-built homes of the period. Prefabrication in the last ten years has been taking on a new life and is being marketed as: Smarter, Faster, Cheaper, Good Design, High Style and Flexible Design. It has been represented as a green way to create new home. The efficient use of space and therefore materials is one of the greenest aspects of prefabricated housing.  The silent film One Week featured Buster Keaton as the groom and Sybil Seely as his new bride in 1920. The newlywed couple received a build-it-yourself house as a wedding gift. The house can be built, supposedly, in “one week.” The movie recounts Keaton’s struggle to assemble the house. What is missing from the construction process is a craftsman. While the kit-of-parts is complete – expertise, experience, and skill was and is still required to successfully assemble the parts. In 1919, Keaton viewed an industrial documentary named Home Made, which became the inspiration for One Week. One Week was essentially a parody of the film Home Made that was produced by the Ford Motor Co. The movie explained the concept of prefabricated homes, which buyers assembled themselves by following a set of instructions.

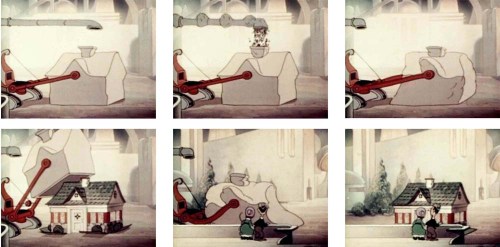

The silent film One Week featured Buster Keaton as the groom and Sybil Seely as his new bride in 1920. The newlywed couple received a build-it-yourself house as a wedding gift. The house can be built, supposedly, in “one week.” The movie recounts Keaton’s struggle to assemble the house. What is missing from the construction process is a craftsman. While the kit-of-parts is complete – expertise, experience, and skill was and is still required to successfully assemble the parts. In 1919, Keaton viewed an industrial documentary named Home Made, which became the inspiration for One Week. One Week was essentially a parody of the film Home Made that was produced by the Ford Motor Co. The movie explained the concept of prefabricated homes, which buyers assembled themselves by following a set of instructions.  This sequence of stills are from the 1938 cartoon All’s Fair at the Fair. What is enlightening about the cartoon is not the house that is being produced. The product of the house resembles the prefabricated homes that Sears produced- which looked as if they were produced by hand. What is thought-provoking is the depiction of the machine that produced the homes. The machine that produces the houses was manufactured to make exact copies much like a factory assembly line. The new technology introduces speed to the production of homes while bringing the factory to the site. The new technology does not change the style of each home. The architect Frank Lloyd Wright wrote the article “The Art and Craft of the Machine, for the magazine Brush and Pencil in 1901 where he cautioned that schools had not bound science and art by truly introducing the artist to their tools. He noted that artists were disconnected from their tools and therefore disconnected from their craft. He wished for materials to show their inherent beauty as he exposed concrete, stone, brick, cast concrete block, and the natural grain of wood. He did not design a flexible system, but instead created different Usonian designs. Usonian was Wright’s word for American.

This sequence of stills are from the 1938 cartoon All’s Fair at the Fair. What is enlightening about the cartoon is not the house that is being produced. The product of the house resembles the prefabricated homes that Sears produced- which looked as if they were produced by hand. What is thought-provoking is the depiction of the machine that produced the homes. The machine that produces the houses was manufactured to make exact copies much like a factory assembly line. The new technology introduces speed to the production of homes while bringing the factory to the site. The new technology does not change the style of each home. The architect Frank Lloyd Wright wrote the article “The Art and Craft of the Machine, for the magazine Brush and Pencil in 1901 where he cautioned that schools had not bound science and art by truly introducing the artist to their tools. He noted that artists were disconnected from their tools and therefore disconnected from their craft. He wished for materials to show their inherent beauty as he exposed concrete, stone, brick, cast concrete block, and the natural grain of wood. He did not design a flexible system, but instead created different Usonian designs. Usonian was Wright’s word for American.  The James Mcbean residence in Rochester, Minnesota is a style No. 2 prefabricated Usonian home that was built in 1957. The language of Wright’s earlier non-prefabricated Usonian homes is reflected in the later Marshall Erdman Prefab Houses. The prefabricated homes were designed in 1954 using standard dimension construction materials such as the 4 foot by 8 foot materials. There were three Usonian house types designed by Wright, but only two of the types were put into production and sold. The architect Buckminster Fuller dreamed that new technology was going to solve Americans housing needs as it gave humans an advantage against the elements and minimized drudgery. He approached the housing shortage as a design problem to be solved through engineering. Fuller’s designs were connected to the new technology of the aviation industry as can be seen in the material choices and riveted connection details. Fuller often asked the question “How much does your house weigh?” His question would have been moot if new technology had not produced lightweight and strong materials.

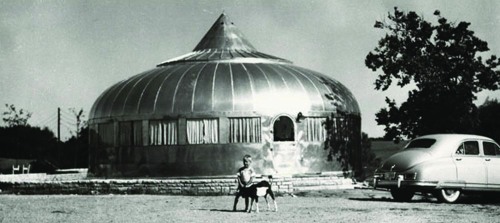

The James Mcbean residence in Rochester, Minnesota is a style No. 2 prefabricated Usonian home that was built in 1957. The language of Wright’s earlier non-prefabricated Usonian homes is reflected in the later Marshall Erdman Prefab Houses. The prefabricated homes were designed in 1954 using standard dimension construction materials such as the 4 foot by 8 foot materials. There were three Usonian house types designed by Wright, but only two of the types were put into production and sold. The architect Buckminster Fuller dreamed that new technology was going to solve Americans housing needs as it gave humans an advantage against the elements and minimized drudgery. He approached the housing shortage as a design problem to be solved through engineering. Fuller’s designs were connected to the new technology of the aviation industry as can be seen in the material choices and riveted connection details. Fuller often asked the question “How much does your house weigh?” His question would have been moot if new technology had not produced lightweight and strong materials.  The design for Fuller’s Dymaxion house was based on his 1927 plan for a mass-produced house called the Dymaxion Dwelling Machine. The word Dymaxion was created by a marketing wordsmith to help advertise Fullers house design. The three blended words are dynamic, maximum, and tension. Buckminster Fuller designed the “Wichita House,” in 1946 and it was erected near Wichita in Rose Hill, Kansas, in 1948. The Beech Aircraft Company constructed the house to demonstrate affordable, prefabricated housing that would take advantage of World War II surplus materials. The structure was made of aluminum and designed to withstand the elements, including a Kansas tornado. This model was one of only two prototypes ever produced. In 1991 the William Graham family donated it to the Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan. The architect Walter Gropius transformed the Grand-Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar Germany into the Bauhaus. The intent of the Bauhaus was to combine art and craft often with industrial applications. His own house in Lincoln, Massachusetts would follow the Bauhaus principles and reflect an International Modernism that showed a desire for maximum efficiency and simplicity. As early as 1923 at the Bauhaus in Germany, Gropius had been working with standardization of building blocks for prefabricated houses. Gropius formed the individual building units with the intent to create variety.

The design for Fuller’s Dymaxion house was based on his 1927 plan for a mass-produced house called the Dymaxion Dwelling Machine. The word Dymaxion was created by a marketing wordsmith to help advertise Fullers house design. The three blended words are dynamic, maximum, and tension. Buckminster Fuller designed the “Wichita House,” in 1946 and it was erected near Wichita in Rose Hill, Kansas, in 1948. The Beech Aircraft Company constructed the house to demonstrate affordable, prefabricated housing that would take advantage of World War II surplus materials. The structure was made of aluminum and designed to withstand the elements, including a Kansas tornado. This model was one of only two prototypes ever produced. In 1991 the William Graham family donated it to the Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan. The architect Walter Gropius transformed the Grand-Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar Germany into the Bauhaus. The intent of the Bauhaus was to combine art and craft often with industrial applications. His own house in Lincoln, Massachusetts would follow the Bauhaus principles and reflect an International Modernism that showed a desire for maximum efficiency and simplicity. As early as 1923 at the Bauhaus in Germany, Gropius had been working with standardization of building blocks for prefabricated houses. Gropius formed the individual building units with the intent to create variety.  Both Walter Gropius and Konrad Wachsmann moved to the US after the Nazis closed the Bauhaus. They both formed the General Panel Corporation (the name reflects not only the name General Motors but also the intent of assembly line production). Wachsmann worked on the connection details and the corporation was subsidized by the US government. Part of the reason for the failure of the system is that “Wachsmann never stopped designing the connection details. Wachsmann was delayed at each stage by this search for the ideal, it took much too long to move from initial concept to the final stage of actual production.”

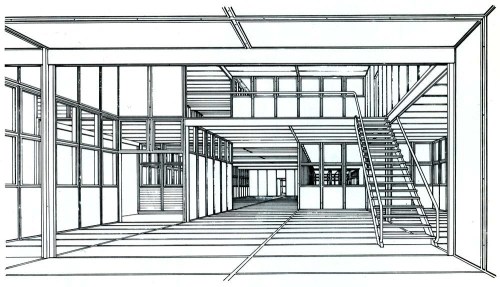

Both Walter Gropius and Konrad Wachsmann moved to the US after the Nazis closed the Bauhaus. They both formed the General Panel Corporation (the name reflects not only the name General Motors but also the intent of assembly line production). Wachsmann worked on the connection details and the corporation was subsidized by the US government. Part of the reason for the failure of the system is that “Wachsmann never stopped designing the connection details. Wachsmann was delayed at each stage by this search for the ideal, it took much too long to move from initial concept to the final stage of actual production.”  The General Panel Corporation panels were designed to be a kit-of-parts that could be used to make site-specific housing. This interior drawing shows a two-story design using the panel system. This reflects Gropius’ fascination with the Japanese house. It makes sense that Gropius wrote the forward to Heinrich Engel’s 1964 book The Japanese House: A Tradition for Contemporary Architecture.

The General Panel Corporation panels were designed to be a kit-of-parts that could be used to make site-specific housing. This interior drawing shows a two-story design using the panel system. This reflects Gropius’ fascination with the Japanese house. It makes sense that Gropius wrote the forward to Heinrich Engel’s 1964 book The Japanese House: A Tradition for Contemporary Architecture.  The General Panel test house was a single level home. With the exception of the recessed entry, there is little articulation on the surface of the exterior.

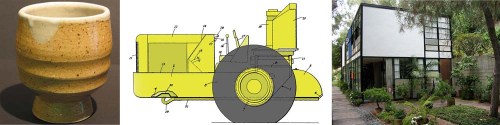

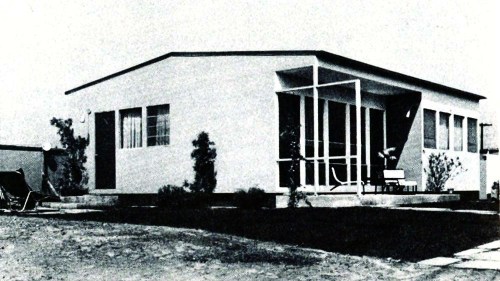

The General Panel test house was a single level home. With the exception of the recessed entry, there is little articulation on the surface of the exterior.  Charles and Ray Eames opened an office in Venice California where they created films, toys, furniture and architecture. Charles went to Cranbrook and studied under Eero Saarenen and would be friends with Eliel Saarenen. Charles was trained as an architect and Ray was trained as a painter. Charles and Ray designed and built the Case Study House No. 8 in Venice, California in 1948. Case Study House No. 8, was one of roughly two dozen homes built as part of a program that was spearheaded by John Entenza, the publisher of Arts and Architecture magazine. While the house was not technically prefabricated, it did take on much of the language of a prefabricated system through the use of off-the-shelf materials.

Charles and Ray Eames opened an office in Venice California where they created films, toys, furniture and architecture. Charles went to Cranbrook and studied under Eero Saarenen and would be friends with Eliel Saarenen. Charles was trained as an architect and Ray was trained as a painter. Charles and Ray designed and built the Case Study House No. 8 in Venice, California in 1948. Case Study House No. 8, was one of roughly two dozen homes built as part of a program that was spearheaded by John Entenza, the publisher of Arts and Architecture magazine. While the house was not technically prefabricated, it did take on much of the language of a prefabricated system through the use of off-the-shelf materials.  The direction will now shift from prefabricated housing to making tools to make things. The machine and the craftsman are integral to creating not only the end product but the selection and creation of the tools. These artist’s tools are handmade. The rhythm of the kick-wheel, the shape of the hand tools and the shape of the salt-kiln all contribute to the final product. The tools selected and created have an impact on the final products of bowls, cups, teapots and vases. The selection of tools and the making of tools by the craftsman is of great importance. The artist, artisan, architect or craftsman should be as close to their tools as possible if they wish to control the outcome. When creating pottery on a wheel for example, the hands directly connect to the clay and the simple tools are the hands. These are tools and not machines, but together they often form a mechanized process. The artist often crafts with simple tools in order to have control over the end product. The machine often enters into the crafting of the products as well. While there is much control attempted, many mechanized processes enter into production such as the mining of the clay and the minerals for the glazes. Machines can elevate some of the time-intensive and laborious tasks.

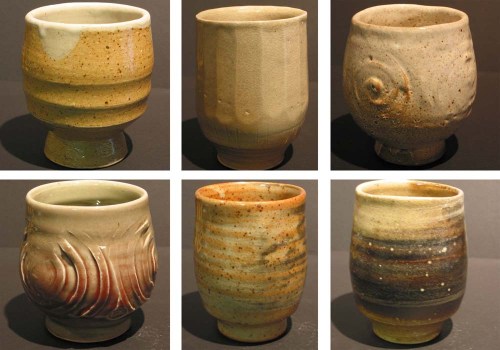

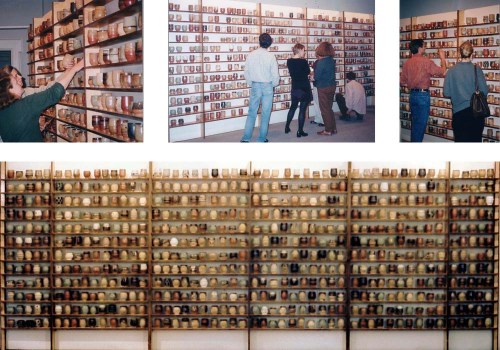

The direction will now shift from prefabricated housing to making tools to make things. The machine and the craftsman are integral to creating not only the end product but the selection and creation of the tools. These artist’s tools are handmade. The rhythm of the kick-wheel, the shape of the hand tools and the shape of the salt-kiln all contribute to the final product. The tools selected and created have an impact on the final products of bowls, cups, teapots and vases. The selection of tools and the making of tools by the craftsman is of great importance. The artist, artisan, architect or craftsman should be as close to their tools as possible if they wish to control the outcome. When creating pottery on a wheel for example, the hands directly connect to the clay and the simple tools are the hands. These are tools and not machines, but together they often form a mechanized process. The artist often crafts with simple tools in order to have control over the end product. The machine often enters into the crafting of the products as well. While there is much control attempted, many mechanized processes enter into production such as the mining of the clay and the minerals for the glazes. Machines can elevate some of the time-intensive and laborious tasks.  The making of tools and selection of tools the by a craftsman is of great importance because the tools selected directly connect with those that use the resulting product… in this case salt-fired cups. One of the directions of this thesis was to express the multiplicity of production, not machine-production but rather craftsman-production.

The making of tools and selection of tools the by a craftsman is of great importance because the tools selected directly connect with those that use the resulting product… in this case salt-fired cups. One of the directions of this thesis was to express the multiplicity of production, not machine-production but rather craftsman-production.  While multiplicity does not automatically translate to artful expression, it is difficult to connect with those that you are producing for without the feedback loop of producing, experiencing, and fine-tuning. While a lip of a drinking cup may, for example, be appealing to the eye, if it dribbles liquid on the user, it quickly becomes a pencil holder and fails at its intended purpose.

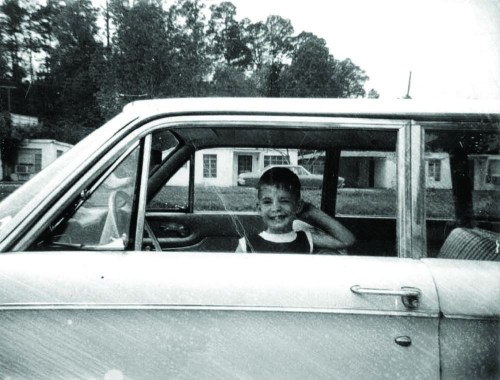

While multiplicity does not automatically translate to artful expression, it is difficult to connect with those that you are producing for without the feedback loop of producing, experiencing, and fine-tuning. While a lip of a drinking cup may, for example, be appealing to the eye, if it dribbles liquid on the user, it quickly becomes a pencil holder and fails at its intended purpose.  As I spoke to my parents about my prefabricated housing research, they noted that we lived in a prefabricated house. My father was a welder for R.G. LeTourneau creating large machines. Note the little white houses in the background behind me as I sit in the Ford Falcon in front of house No. 21. I had always assumed that they were constructed of concrete masonry units aka concrete block. After research, I found that they were each created in a single pour of concrete. My father worked for Robert Gilmore “R.G.” LeTourneau and learned to weld, craft tools, and make machines there. LeTourneau created the largest earth-moving equipment in the world, forestry machines and offshore oilrigs which he created with welding machines and torches as he liked to form them in situ. He also was the first to put large rubber tires on earthmoving equipment instead of the then ubiquitous steel wheels. He worked with Firestone to create the molds for the tires he needed.

As I spoke to my parents about my prefabricated housing research, they noted that we lived in a prefabricated house. My father was a welder for R.G. LeTourneau creating large machines. Note the little white houses in the background behind me as I sit in the Ford Falcon in front of house No. 21. I had always assumed that they were constructed of concrete masonry units aka concrete block. After research, I found that they were each created in a single pour of concrete. My father worked for Robert Gilmore “R.G.” LeTourneau and learned to weld, craft tools, and make machines there. LeTourneau created the largest earth-moving equipment in the world, forestry machines and offshore oilrigs which he created with welding machines and torches as he liked to form them in situ. He also was the first to put large rubber tires on earthmoving equipment instead of the then ubiquitous steel wheels. He worked with Firestone to create the molds for the tires he needed.  The 1922 Mountain Mover was designated A Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark. This steel-wheeled machine was an early piece of his equipment that reflects LeTourneau’s kit-of-parts which consisted of the welding machine and the torch. There were no rivets used in LeTourneau’s machines. His tools also included not only physical constructions but also correspondence courses in metallurgy as well as learning through his experiences. He built upon his knowledge as he fine-tuned his machines. Most all of his machines were designed for earth-moving and there was always continued experimentation. If a machine did not work as planned, he would put it aside and approach it later when a new task presented itself.

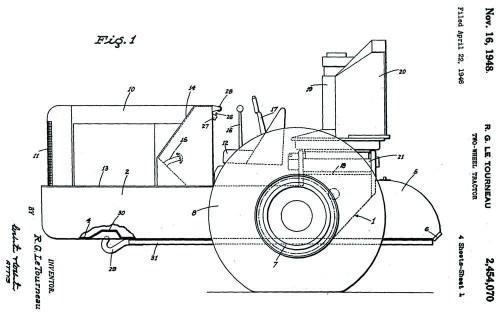

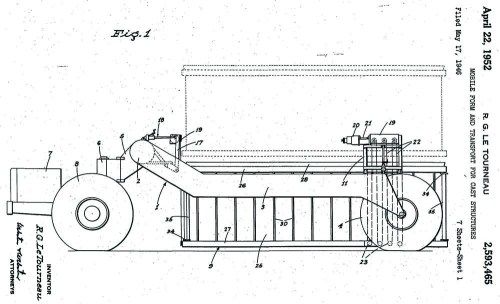

The 1922 Mountain Mover was designated A Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark. This steel-wheeled machine was an early piece of his equipment that reflects LeTourneau’s kit-of-parts which consisted of the welding machine and the torch. There were no rivets used in LeTourneau’s machines. His tools also included not only physical constructions but also correspondence courses in metallurgy as well as learning through his experiences. He built upon his knowledge as he fine-tuned his machines. Most all of his machines were designed for earth-moving and there was always continued experimentation. If a machine did not work as planned, he would put it aside and approach it later when a new task presented itself.  The patented Two-Wheel Tractor was named the Tournapull. LeTourneau used the prefix “Touna” to name things in which he had pride. This machine was invented as the prime-mover for other pieces of equipment, some of which had yet to be invented. The Mobile Form for Cast Structures was a house laying machine that he named the Tournalayer. LeTourneau designed and built the Tournalayer as a machine to form houses in a single pour of concrete with the steel reinforcement, electricity and plumbing embedded within the walls. The first two communities were for his employees in Vicksburg, Mississippi and Longview, Texas.

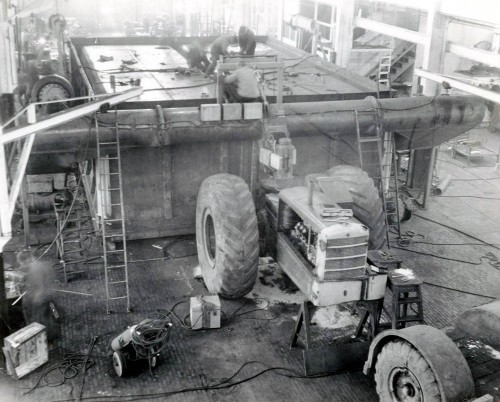

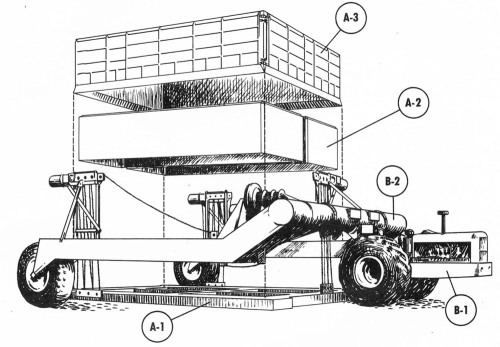

The patented Two-Wheel Tractor was named the Tournapull. LeTourneau used the prefix “Touna” to name things in which he had pride. This machine was invented as the prime-mover for other pieces of equipment, some of which had yet to be invented. The Mobile Form for Cast Structures was a house laying machine that he named the Tournalayer. LeTourneau designed and built the Tournalayer as a machine to form houses in a single pour of concrete with the steel reinforcement, electricity and plumbing embedded within the walls. The first two communities were for his employees in Vicksburg, Mississippi and Longview, Texas.  Tournalayer No. 2 was handcrafted in the factory and each of the components was hand fitted to work with the other components. The sections are hand-crafted rather than manufactured because each one of these machines was hand-made as essentially a one-off that was fine-tuned with new each iteration of houses. There was a feedback loop of creating, making, and using the homes.

Tournalayer No. 2 was handcrafted in the factory and each of the components was hand fitted to work with the other components. The sections are hand-crafted rather than manufactured because each one of these machines was hand-made as essentially a one-off that was fine-tuned with new each iteration of houses. There was a feedback loop of creating, making, and using the homes.  LeTourneau’s welders crafted the Tournalayer in order for others to create homes and form communities. The welders were essentially making a tool that made homes in locations that had yet to be decided. There was an efficiency in numbers and creating one-offs with this machine was not a resourceful use of materials. In effect, the Tournalayer was not a house making tool, but a community forming tool.

LeTourneau’s welders crafted the Tournalayer in order for others to create homes and form communities. The welders were essentially making a tool that made homes in locations that had yet to be decided. There was an efficiency in numbers and creating one-offs with this machine was not a resourceful use of materials. In effect, the Tournalayer was not a house making tool, but a community forming tool.  The Tournalayer consists of many parts that cast, deliver, and place the house. The main parts are the Tournapull and the Tournalayer. The Tournalayer consists of a frame, inner and outer molds and a base upon which they sit. The cast concrete house has an integral footer, inner and outer walls, and a roof/ ceiling. Rube Goldberg was a cartoonist who created cartoons that expressed the idea of completing a simple task in the most complicated way. Most all of his drawings were machines that had many components that created a complex sequence of events. Robert Gilmore earned the nickname “R.G.” at his Peoria, Illinois plant when one of his foremen thought “R.G.” better stood for Rube Goldberg.

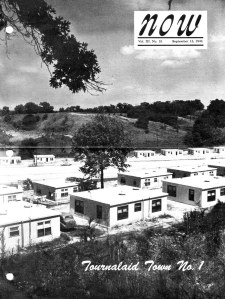

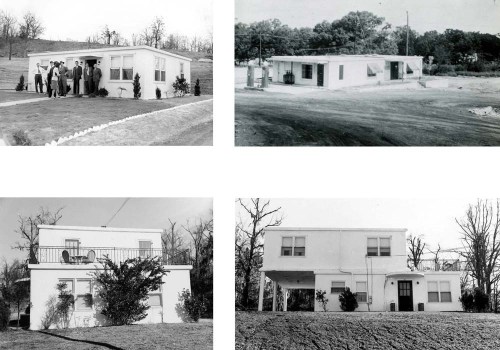

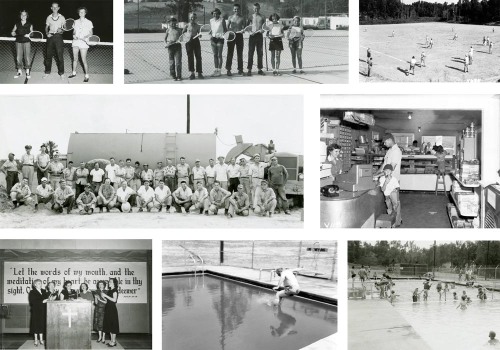

The Tournalayer consists of many parts that cast, deliver, and place the house. The main parts are the Tournapull and the Tournalayer. The Tournalayer consists of a frame, inner and outer molds and a base upon which they sit. The cast concrete house has an integral footer, inner and outer walls, and a roof/ ceiling. Rube Goldberg was a cartoonist who created cartoons that expressed the idea of completing a simple task in the most complicated way. Most all of his drawings were machines that had many components that created a complex sequence of events. Robert Gilmore earned the nickname “R.G.” at his Peoria, Illinois plant when one of his foremen thought “R.G.” better stood for Rube Goldberg.  The Vicksburg community was shaped by the earthmoving equipment and the building structures were created with the Tournalayer. A community laundry, around 100 homes, a grocery store/ post office and a swimming pool were created with the Tournalayer. Many of the craftsmen in the community were men who had lived in homes with no running water, plumbing or telephones. In several instances, this was the first time many lived in homes with these services. The homes also provided heated floors. Modern not only reflects the clean exterior skin of these minimal homes, but modern also reflects the amenities that were within.

The Vicksburg community was shaped by the earthmoving equipment and the building structures were created with the Tournalayer. A community laundry, around 100 homes, a grocery store/ post office and a swimming pool were created with the Tournalayer. Many of the craftsmen in the community were men who had lived in homes with no running water, plumbing or telephones. In several instances, this was the first time many lived in homes with these services. The homes also provided heated floors. Modern not only reflects the clean exterior skin of these minimal homes, but modern also reflects the amenities that were within.  The members of the community simply called it “LeTourneau.” “LeTourneau” was a place. The community was formed with machines by the LeTourneau employees. There were several Tournalayer Communities. Each had very different site plans as well as building configurations.

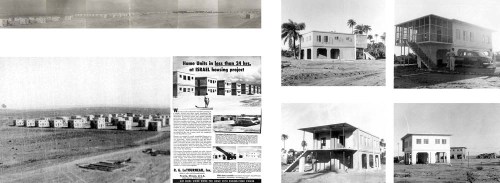

The members of the community simply called it “LeTourneau.” “LeTourneau” was a place. The community was formed with machines by the LeTourneau employees. There were several Tournalayer Communities. Each had very different site plans as well as building configurations.  Two-story Tournalaid houses were constructed in Beer Shiva, Israel and were created on lands that were previously occupied by nomadic people. They were arranged on a rigid grid. The homes survive but have been incorporated into larger structures. French Morocco homes were designed for the coast of the Atlantic Ocean and the lower floor is open in the event of rising water. The main living area is on the upper level.

Two-story Tournalaid houses were constructed in Beer Shiva, Israel and were created on lands that were previously occupied by nomadic people. They were arranged on a rigid grid. The homes survive but have been incorporated into larger structures. French Morocco homes were designed for the coast of the Atlantic Ocean and the lower floor is open in the event of rising water. The main living area is on the upper level.  These Tournalayer homes are likely part of the Peron 5 year plan and are most likely located in Argentina. The plan occurred from 1947 to 1951. The base structure that the Tournalayer provided was adapted and supplemented. The homes have larger overhangs of about a foot and a parapet has been added with an inset medallion of the face of the home. The roof has become occupiable through the addition of a set of stairs at the rear of the home. While these houses were likely constructed as low-income housing, the amenities had evolved from the first houses in Vicksburg and Longview. A feedback loop was used by reflecting on the previous houses and apply the new information.

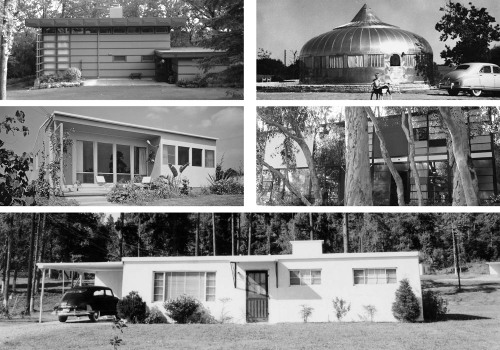

These Tournalayer homes are likely part of the Peron 5 year plan and are most likely located in Argentina. The plan occurred from 1947 to 1951. The base structure that the Tournalayer provided was adapted and supplemented. The homes have larger overhangs of about a foot and a parapet has been added with an inset medallion of the face of the home. The roof has become occupiable through the addition of a set of stairs at the rear of the home. While these houses were likely constructed as low-income housing, the amenities had evolved from the first houses in Vicksburg and Longview. A feedback loop was used by reflecting on the previous houses and apply the new information.  Philosophies of premanufactured homes was diverse in the 1950s as different materials and different construction methods were used. Frank Lloyd Wright designed with lineaments and was rooted in the arts and crafts. Site-specific designs were important to Wright. Buckminster Fuller was rooted in engineering, technology and manufacturing. His systems were non-site specific and were derived from aviation technology. Walter Gropius was interested in the arts and crafts and introducing them into manufacturing. He helped create a system that could be applied to different locations to create a site-specific design. Charles and Ray Eames both worked not to produce a mass-produced system, but rather formed a language of ready-made parts. R.G. LeTourneau moved the factory to the construction site with the creation of the Tournalayer. He had a hands-on approach by creating a machine that was used by others to form communities throughout the world. He was intent on providing durable homes with modern amenities for the members in the communities.

Philosophies of premanufactured homes was diverse in the 1950s as different materials and different construction methods were used. Frank Lloyd Wright designed with lineaments and was rooted in the arts and crafts. Site-specific designs were important to Wright. Buckminster Fuller was rooted in engineering, technology and manufacturing. His systems were non-site specific and were derived from aviation technology. Walter Gropius was interested in the arts and crafts and introducing them into manufacturing. He helped create a system that could be applied to different locations to create a site-specific design. Charles and Ray Eames both worked not to produce a mass-produced system, but rather formed a language of ready-made parts. R.G. LeTourneau moved the factory to the construction site with the creation of the Tournalayer. He had a hands-on approach by creating a machine that was used by others to form communities throughout the world. He was intent on providing durable homes with modern amenities for the members in the communities.